El Salvador brings to mind, for most everyone over 25 years of age, the very recent civil war that it experienced. Traveling in this country for the past two weeks, there are both constant remnants and reminders of the war—which really began planting its roots a century before—as well as an obvious moving forward. In fact, after the peace accord was signed in 1992 ending the war, the people of this small country began immediately to leave the fighting behind and get on to the business of rebuilding their lives, and their nation.

Today, a mere 21 years later, the highways are the best in Central America and a pretty decent tourism infrastructure exists. True, outside of tour guides and large San Salvador hotels, many people speak no English (but you didn’t come to Central America to hear English, did you?); elements of service to the visitor and ease of traveling could be improved; but overall, for a mere two decades into creating a new face that invites visitors, it’s highly impressive how far they have come, so fast. I highly recommend a visit here for the traveler interested in Central/Latin America—it offers a vast natural beauty, outgoing and interested people, and a fair amount of diversity for a country that is smaller than San Diego County. And although of course I would recommend a reasonable amount of safety precautions (don’t drive or roam the streets of San Salvador at night, for example), I for one felt extremely safe and at ease here.

Today, a mere 21 years later, the highways are the best in Central America and a pretty decent tourism infrastructure exists. True, outside of tour guides and large San Salvador hotels, many people speak no English (but you didn’t come to Central America to hear English, did you?); elements of service to the visitor and ease of traveling could be improved; but overall, for a mere two decades into creating a new face that invites visitors, it’s highly impressive how far they have come, so fast. I highly recommend a visit here for the traveler interested in Central/Latin America—it offers a vast natural beauty, outgoing and interested people, and a fair amount of diversity for a country that is smaller than San Diego County. And although of course I would recommend a reasonable amount of safety precautions (don’t drive or roam the streets of San Salvador at night, for example), I for one felt extremely safe and at ease here.

One of the highlights of our visit was a day that we spent on the Ruta de la Paz, the Route of Peace. This route took us up into the far northeastern reaches of the country, the Morazán area only 9 kilometers from the Honduran border, where the FMLN guerrilla revolutionary stronghold was, and where some of the bloodiest, most brutal events of the war took place.

The first stop was the Museo de la Revolucion in Perquin—the Revolution Museum. Here, in a simple concrete building and surrounding plot of land, hundreds of artifacts from the war are collected in a way that tells a violent yet poignant story. Immediately upon entering, we were greeted by Jose Oscar, who we soon learned is a former FMLN guerrilla himself. He showed us around the museum, explaining the pieces of history to us and telling the stories of one of his country’s most difficult periods.*

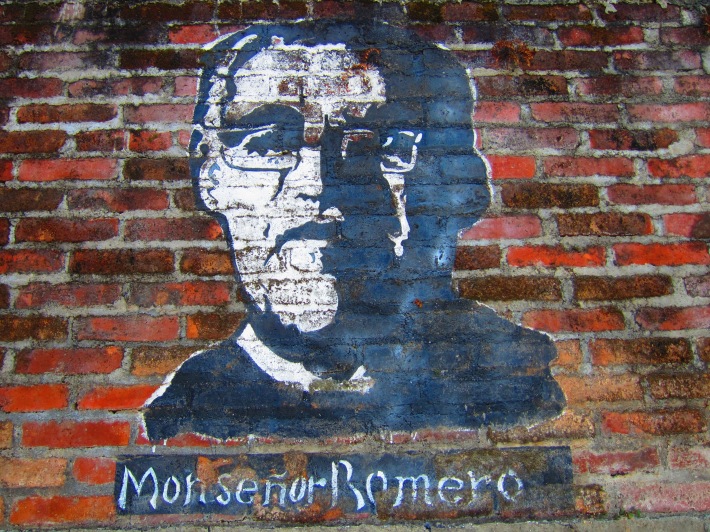

“This was Monsignor Romero’s burial,” Jose told us in Spanish, pointing to a photo of the priest whose 1980 assassination was the lit match that set off a full-scale war. “It all started back in the 80s with small guns and homemade weapons, that is how it all got started. From then it went on and on.”

“This was Monsignor Romero’s burial,” Jose told us in Spanish, pointing to a photo of the priest whose 1980 assassination was the lit match that set off a full-scale war. “It all started back in the 80s with small guns and homemade weapons, that is how it all got started. From then it went on and on.”

Jose led us through the building, explaining various photos and items in his unusual combination of Spanish, local dialect and old Castilian. It was a somber experience, but yet an important piece of history that should not be overlooked or forgotten. One aspect that really struck me was how many women were part of the revolution for the rights of the farmers, workers, poor and indigenous—both as activists and on the front lines, as fighters.

Next, Jose showed us the room and adjoining porch where the artillery was on display. “We never had any of those things during the war,” he said, speaking of tanks and airplanes; pointing instead to the guns and homemade bombs. “The guerrilla never had cars or airplanes. Everything was on foot, so from the start, it was much harder for us.” Outside the museum was a huge bomb crater from a government missile, in a site where six bombs were dropped from airplanes in 1981.

“And this one fell over here,” Jose said, pointing to the crater. “It’s been 31 years. Little by little we filled the holes, planted trees, but everything around us was complete destruction. When the bombs were dropped, everyone and everything was gone.“

At the end Jose, who is 50 years old, told his own personal story. In 1984, he was shot four or five times in the leg by machine gun fire. He walked for many days on it before he was able to find medical attention; sometimes only eating every few days, and walking only at night to avoid discovery. He led me back into the museum building to show a photo on the wall titled “Heroes and Martyrs,” and pointed to a face among a line of soldiers. “That is me. Do you think you are guilty?” Jose asked rhetorically, I believe of his own actions. “I said, no, it’s not the people’s fault, war comes as a direct result of those who govern. They can do business, sell weapons and access new technology to build new weapons.”

At the end Jose, who is 50 years old, told his own personal story. In 1984, he was shot four or five times in the leg by machine gun fire. He walked for many days on it before he was able to find medical attention; sometimes only eating every few days, and walking only at night to avoid discovery. He led me back into the museum building to show a photo on the wall titled “Heroes and Martyrs,” and pointed to a face among a line of soldiers. “That is me. Do you think you are guilty?” Jose asked rhetorically, I believe of his own actions. “I said, no, it’s not the people’s fault, war comes as a direct result of those who govern. They can do business, sell weapons and access new technology to build new weapons.”

I am the law and I am the state. I am the morals; the history,

because I have bought it.” ~Francisco Gadiva, Salvadorian poet & writer

From Perquin, we visited the town of El Mozote, a few kilometers down the road. This place is infamous, sadly, for one of the most brutal massacres of Salvador’s Civil War. On December 10, 1981, government military special forces (who had blocked the town in), woke everyone in the village in the early morning hours and ordered them into the central park. There they were divided into groups of men, women and children. At dawn, the executions began with the men. The women and older girls were taken nearby where they were raped before they were also shot.

Finally, approximately 140 children were herded into a church which soldiers then set on fire. All in all, around 1,000 people died that day in northern El Salvador.

The battalion which conducted this genocide had been trained and supported by the United States, with the personal authorization of President Ronald Reagan. Both Reagan and the Salvadoran government denied that the massacre had taken place, and covered it up for many years.

There was just one problem for them: There had been a survivor.

A survivor. As in one person. Out of a thousand.

Her name was Rufina Amaya Mirquez. She escaped because she had hidden in a tree—from where she had to listen to her husband, her four children, her neighbors and everyone she knew being killed. Rufina went immediately to the international media, but the story was still denied. In 1993, a forensics team was sent in to excavate the area. Skull by charred skull, Rufina’s story was proven true as the bodies were uncovered. In 2006, the International Committee for Human Rights formally recognized the El Mozote Massacre.

In the town, we stopped by the very small museum dedicated to Rufina Amaya. Blink and you would miss it. The museum is actually in the house of Rufina’s daughter, and is filled with newspaper accounts and international awards and recognition later given to the lone survivor of El Mozote.

There I met Rufina’s granddaughter, Lesley. A solemn teenager, Lesley showed me her grandmother’s sewing machine, her shoes, and the honors given her.

“Why should I be afraid of telling the truth?” Rufina told a newspaper years after the massacre. “It was a fact what they have done, and we have to be strong to say it. Today I tell the story, but then I could not. I felt a lump and pain in my heart that I could not speak. All I did was mourn.”

It was a very somber day—but some moments in history should never be forgotten.

On the El Mozote memorial are these words:

We are not dead.

We are with each other,

with you and

with all of humanity.

* A very special thanks to Adriana Sibaja, who so generously translated the words of Jose Oscar for this story.